How Not Gendering My Kids Led To My First 100-Day Art Challenge

And what I'm taking away from the experience

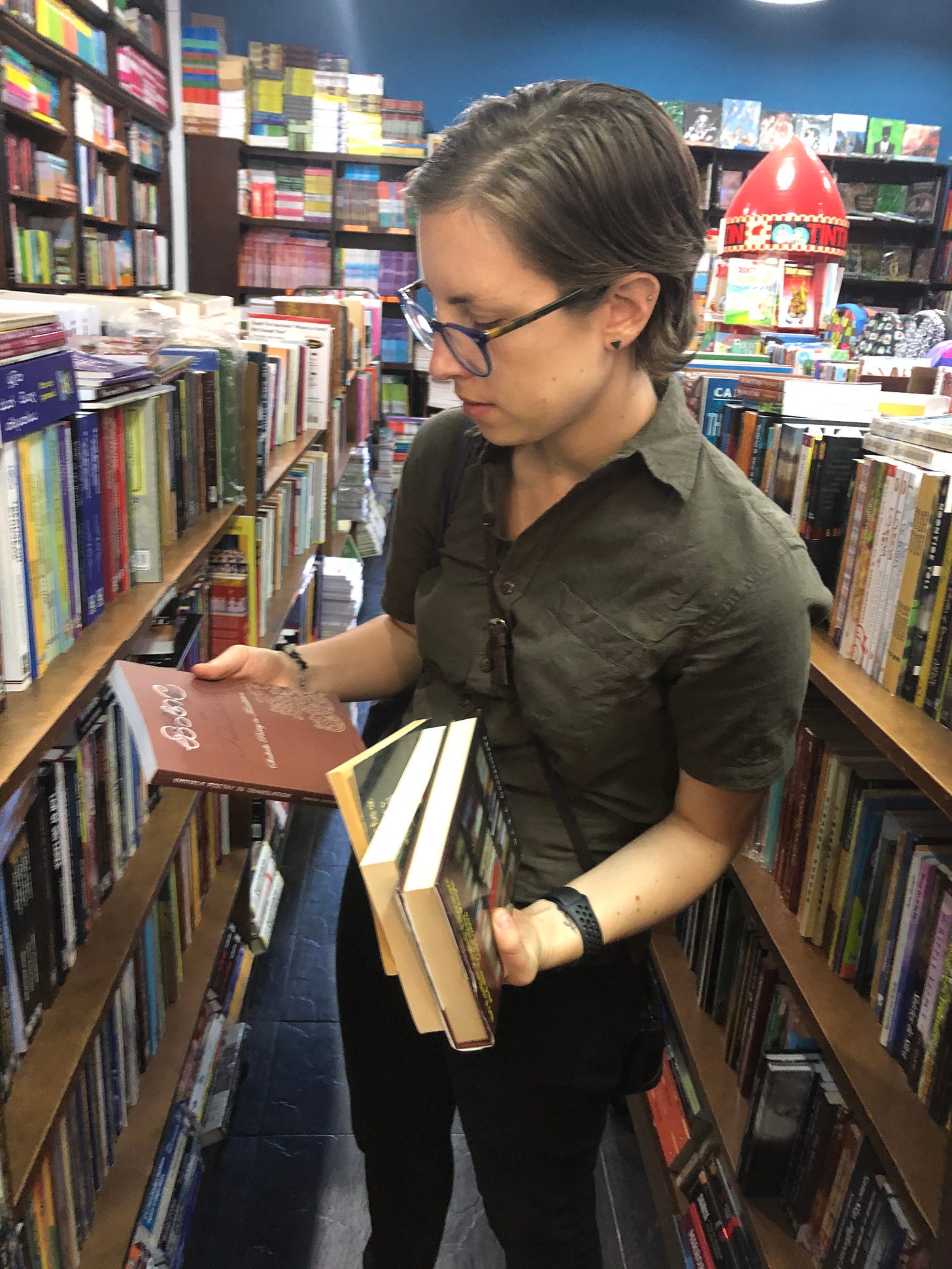

The shop resided in a loft, overlooking the street below. To get to it, we had to walk through another business. The clothes were lovely, made in lightweight linen and cotton, in neutral shades, hanging from simple metal-work wracks. We each took a few things into the dressing rooms and tried them on. My spouse quickly found a few button-down shirts that fit well and in colors that suited his complexion.

I had chosen a black linen shirt, a long dark green blouse, and an orange dress. The shirt hugged me uncomfortably under the arms, but it was the largest size they had and it looked nice on me—I could see that in the three floor-length mirrors. The green blouse slipped on easily, and was closer to my comfort—loose, not rubbing me anywhere.

Last, I tried on the dress.

It fit over my body, but looking in the mirror with it on, I began to sweat, and to feel a keen sense of disembodiment. I was there in the glass, but not as myself. I had managed to conjure the person I’d been striving to be, on and off, for most of my life: a picture of womanhood—smooth, curving, gentle on the eyes. But I was gone. Swallowed up by the vision.

At the time, I didn’t name or describe any of these feelings. I just registered the discomfort I’ve always felt when trying on clothes and did what I’d always done: bought the items despite the fact that I’d struggled to fit the black shirt over my head and that, though I owned quite a few dresses, I rarely chose to wear them.

When I did, I often took them off soon after. Just like when I attempted to apply makeup. It felt so mask-like on my skin. Most times, I would wash it off before even leaving the house. Once I could see my face again, scars and all, I would feel something click back into place in my chest. I was back, able to recognize myself again.

Though my spouse and I were living in Sri Lanka at the time, all of the feelings were the same as they’d been anywhere else.

But trying on that orange dress stuck with me in a way all these previous experiences hadn’t. I couldn’t get the feeling out of my mind. Over the following weeks, I searched online to try to find out if there was a name for what I was feeling. It felt like I didn’t fit myself. Like I was two pieces of the same puzzle, but shaped to mesh with other parts of the tableau’s geography. I could jam the edges together, but would know that I’d done so, remaining aware of the false correspondence.

Was it my body that was the problem?

I had grown up home-schooled, part of a very small, very gender-normative community. Men made the money, women had babies and tended house. These were the expected and accepted roles. I hadn’t been aware of alternatives and spent much of my laundry-doing, dishes-washing, baby-butt-wiping childhood experiencing fits of anger I didn’t understand.

I felt fine in my skin. It was when I put on clothes that felt stereotypically feminine, or painted my nails, or curled my hair that I began to feel very off. It was like slipping on a costume. One that pinched.

Then, one day, lying on our bed in the little room we rented in Colombo, I came across the term non-binary. I’d already been learning about how binaries sustain each other and that they’re often false, extreme poles—and that most things, and people, exist somewhere in the middle. Learning the meaning of the term felt like coming home to myself. Even now, five years later, that feeling of ease replicates itself inside me, reminding me that there is actually a place in language for people like me, who don’t fit the male or female ideal, who don’t see themselves in either, or who see themselves in both.

Figuring this out allowed me to stop trying to fool myself—and others—about what I liked, and launched a process of self-discovery that has brought more body-comfort and self-confidence than I ever felt in the past. It has meant freedom.

Until the next year, when my spouse and I decided we wanted to try to have a child, all of this only meant change for me.

Then, for a class, I read Susan Stryker’s piece about performing transgender rage. In the essay, Stryker recounts witnessing a birth, and the doctor’s pronouncement of the baby’s gender, and how this rang out, for Stryker, as a non-consensual gendering. The baby had had no time to self-discover, to self-define.

The world had already imposed its norms, proclaiming who the child was and would be. Setting the parameters for who they could become.

I have never been one to join challenges set by other people—I don’t usually get anywhere with them. That said, I am very good at sticking to things I set for myself. Recently, that took the form of a 100-day art-making challenge. I didn’t come up with any rules, other than that I had to make something each day for one hundred days straight.

This challenge came about in response to grieving the loss of a 13-year friendship. One of David’s and my more controversial choices for our family has been not to gender our kids. We’ve known their biological sex in each case, even before birth, but haven’t assigned them a gender. (Our older child is three, and still says they’re a “kid” rather than a “girl” or “boy” when asked.)

We figure that they’ll tell us more about who they are when they’re ready for all those self-defining activities, and we’re ready and happy to watch those self-definitions change as they grow—including in regards to their gender identities. For now, we use they/them pronouns for both kids, we have lots of clothes and toys for them to choose from (yay, hand-me-downs!), and each child has multiple given names from which to pick (or not, if they like something else better).

We just want to see who they are and who they become.

My long-time friend couldn’t get on board with this. Despite many conversations explaining our reasoning—conversations that started before my first child had even left my body—she persisted in misgendering them, and even went so far as to suggest we needed to be consulting with a child psychologist about our choice not to assign gender, since she thought this choice might be doing our children permanent harm.

I asked only that she trust that we were doing what we believe is best for our kids, based on our own experiences with gender, lots of reading, and careful thinking. She interpreted that request as disrespectful of her, and refused, and then she walked away from our relationship of more than a decade.

I was six months pregnant with our second child at the time, and very, very hurt. I’m estranged from both of my own parents, and she had filled a lot of the gaps for me over the years—guiding me through the process of transferring to a four-year university from community college, advising me to live with my partner for a while rather than rushing into marriage at just 23 years old, helping me understand what having children could mean (not all drudgery and toil!). We shared trips and jokes and early mornings. I lived with her and her family for three months when I was 21. She was one of the people I most wanted to know my children.

It broke my heart that she could so easily leave my life, and for such an incomprehensible reason—pronouns! I couldn’t help but wonder: Would she have spoken up if the issue had been a more normalized parenting choice, even if she’d viewed it as harmful or wrong? What if I’d been spanking my kids?

I have so much experience with relationships ending, I knew I wouldn’t get anywhere by dwelling on these kinds of questions.

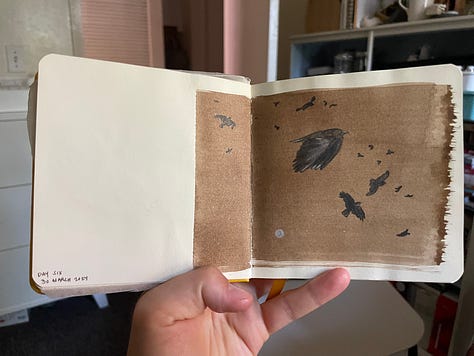

One of the functions of art in my life has been to distract me away from what I can’t change. I needed a plan for moving through the loss, and so, the day after she broke contact, I decided: I would draw or paint or collage or something, every day for 100 days. In this way, I would keep moving through the grief over losing her.

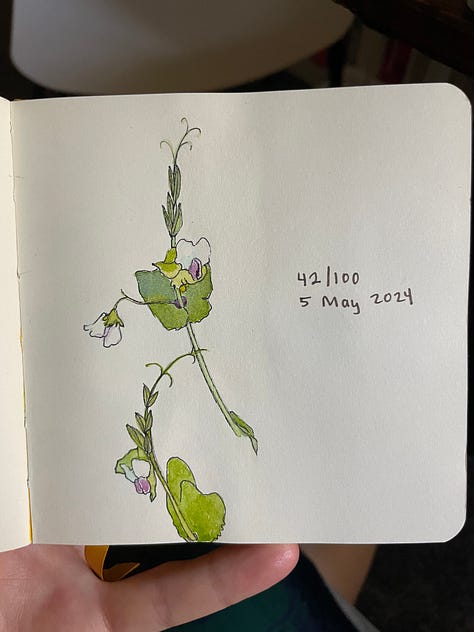

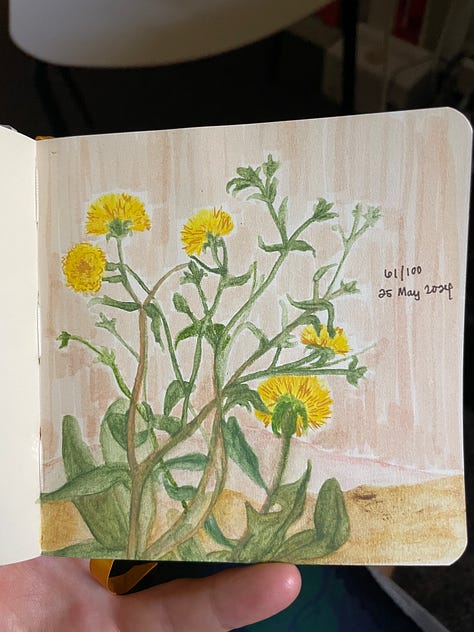

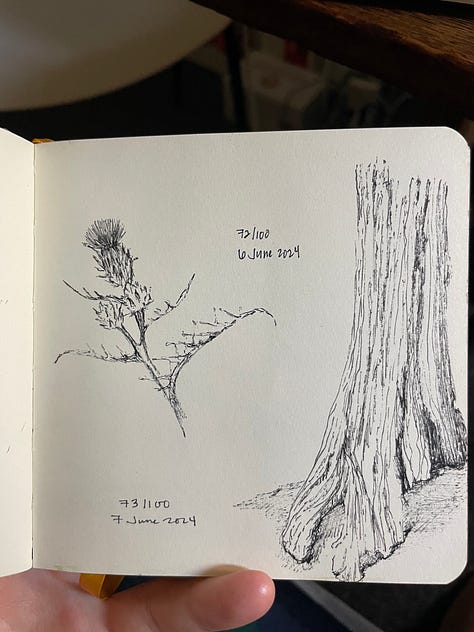

Before starting this challenge, I often felt I should be able to just draw whatever was in front of me, without needing to feel drawn to that thing. But finding something to depict every day for one hundred days got me to look more carefully, becoming more patient with my own observations, as I found what it was I wanted to try to express on the page.

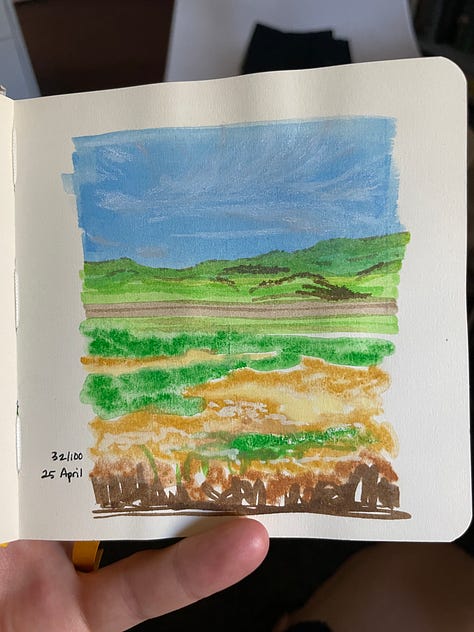

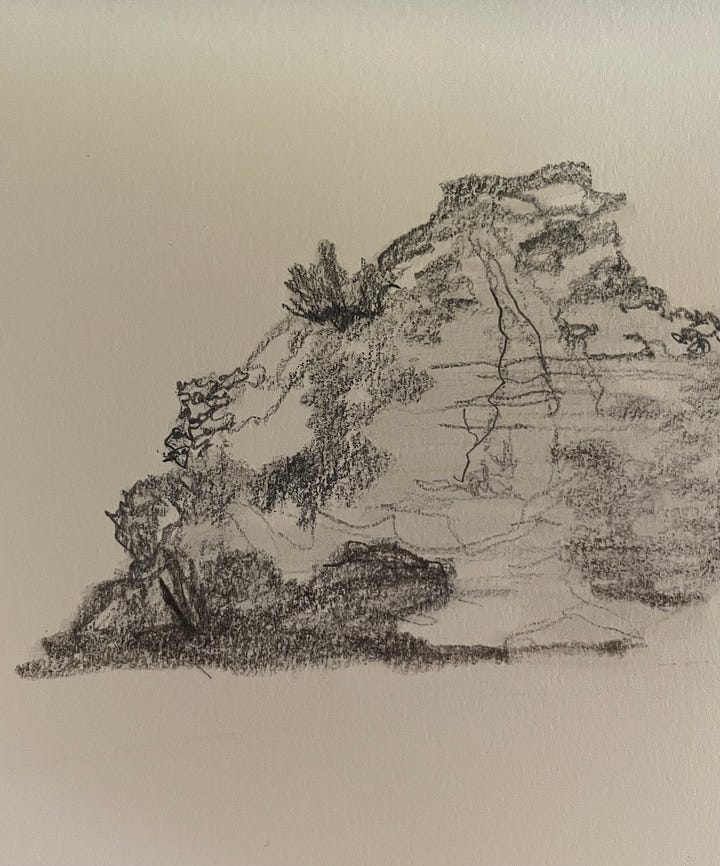

The consistency of the practice lowered my expectations for any single day, and helped me to see that even “bad” drawings could lead to discoveries. On day 77, for example, I did not have a lot of time, I had no subject in front of me (being stuck at my desk), and all I felt pulled to do was to use the side of my pencil to make random shapes. These shapes became birds, which then became a very colorful watercolor-pencil mountainscape. I didn’t like any of what I’d made, but I felt I’d let something out of my system.

The next day (78/100), I got the chance to go draw at David’s workplace (he coordinates an ecological restoration nonprofit), and found myself using the techniques I’d tried out the day before—rotating my pencil, dragging it on its side—and loving the results. Through this, I saw that “technique” can come from aimless play. That’s a big lesson, and one that has completely changed the way I engage my materials.

In the end, after one hundred days, I—of course—was still grieving my friendship.

Grief takes a long time to pass through. But I was able to conclude very early in the process that I had actually been saved from some pain, probably, by going through this experience now. What if she had taken longer to get to this place, and my kids had known her better? This separation would have been their pain, too, if that had been the case. Since it happened while both of my children are still very young, I only need to manage my own feelings about the change.

The person who had been my friend showed me that she could not be one of those people, for me. Learning that—and seeing the contrast with other relationships—has meant that I can choose to put myself more fully into my time with the people who have consistently shown me that they are here for me as a full person. That they can take in the fullness of who I am, and it will only make our relationship stronger.

In addition to those lessons about my art practice, I learned something important about my life, going forward. Something I’ll share with my children as they go through their own heartbreaks and losses. We all need people who can see us for who we really are and not blink.

If you enjoyed this piece, please consider sharing your thoughts in a comment, sending it to someone who might also enjoy it, or leaving me a tip.