Sleep gremlins and artist fears

And what my practices are teaching me about how to live with postpartum depression (again)

This 18th century painting, by Henry Fuseli, is the best depiction I’ve come across of how it feels to “co-sleep” with a growing baby. It’s also a great visual to accompany Karen Russell’s story, “Orange World,” which is itself the best literary portrayal of postpartum depression I’ve come across. Both depression and sleep have been on my mind lately, as I try to figure out the point of making art at all.

I was sitting in our ratty blue armchair a couple of weeks ago—my feet pulled up onto the cushion, trying to focus on playing doctor with my four-year-old kid, very aware that my spouse was about to leave for work and that I would have both kids to myself for the next four or five hours—when my emotions could no longer be contained. They spilled out onto my face, and my child, in the process of describing their* baby doll’s ailment, stopped and said, “Momma, what’s wrong? You look so sad.”

I told them that I was ok, that I just hadn’t been getting enough sleep. And sleep was definitely part of it.

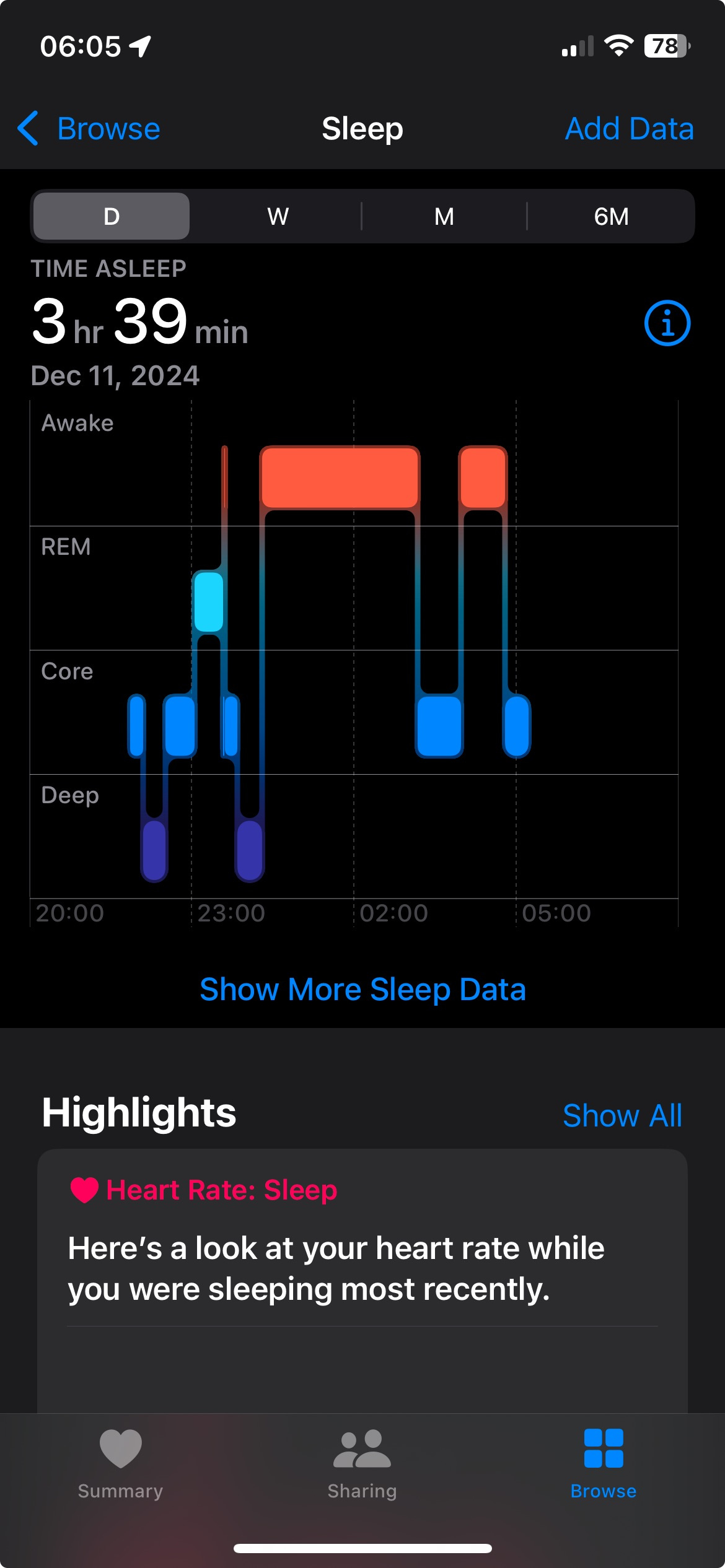

My partner and I both wear smart watches to bed, and so, each morning, we have a picture of how much sleep we got and details about its quality. We wear the watches, and check the data they gather, to better be able to set expectations. Or just to drive ourselves crazy.

Sometimes I’m not sure which.

If you’ve ever had a baby sleep in your room (I see you older sibs!), you know they can have nights when they wake up, a lot. Nap times can also be tricky. I shared a room throughout childhood, and experienced the babyhoods of both my younger sisters. I would often get literally stuck, having gone into our room to get something. My baby sister would stir in her sleep, and I would dash under the crib so she wouldn’t see me and really wake up. My hair would inevitably get tangled in the springs of the structure holding up the crib mattress, and there I would crouch, hoping for silent rescue.

If you’ve never had a baby sleep overnight in your room, imagine this: every hour or so, in the beginning few months of their life, you wake up because there’s someone else there in what had been familiar space, shifting around, babbling and/or crying. You’re not used to this person at all, and so you might sit straight up, interrupting the two minutes of deep sleep you were finally getting. And they might not even be awake. They might, as was the case for my second baby, just not have learned yet how to get their poop out, and so be grunting and clenching their whole tiny body every day around four a.m.

When this new and usually pretty small person does wake up, they either want to eat, have just managed to pee all over the bed, and/or have spit up (sometimes directly into their own ear). Really!

In other words, you’re not just waking up with them when these things happen. You’re also wiping this new person’s butt (in the dark so that they can eventually develop a circadian rhythm matching their parents’). You may need to change sheets and/or shower while holding them. You will definitely need to feed them several times, either from a bottle or from your own body.

Postpartum is a disruptive time.

As parents of two young children, my spouse and I have often been tired. Overall, it has been helpful to know how much sleep we actually managed.

Sometimes I have wished that tracking my inner life was as simple. That there were some device to tip me off before I’ve reached the crisis, letting me know that the crisis is coming. Once this wish shows up, though, the past experiences start also to roll in, reminding me that, actually, there probably were many signs, but that I had stopped paying attention.

Even in that moment, crying in the blue chair while playing hospital, I knew sleep wasn’t the only problem.

Over the days that followed, I started to see all the other signs of PPD that had been right there, but that I had stopped looking out for: high highs and low lows, which had been feeling compressed, a whole cycle happening in the space of a few minutes sometimes; not wanting to make a decision ever again for the rest of my life; not being able to fall asleep, even when I felt exhausted; not finding pleasure in the things that had been sustaining me: morning walks by myself, art-making, writing, eating, sitting with my children.

Last time I recognized PPD in my life, I allowed myself to be absorbed into my then burgeoning art practices (my essay about that time is linked below):

This time, my visual practice is well developed. In fact, all the things that I might have turned to to guide me out of this are already present. They just haven’t been working.

Everything about the way I usually do things has felt too active to help me work through the mourning that needs to happen—for all of the things that have filled me with grief this time around, and due to the recurrent recognition of mortality that giving birth prompts.

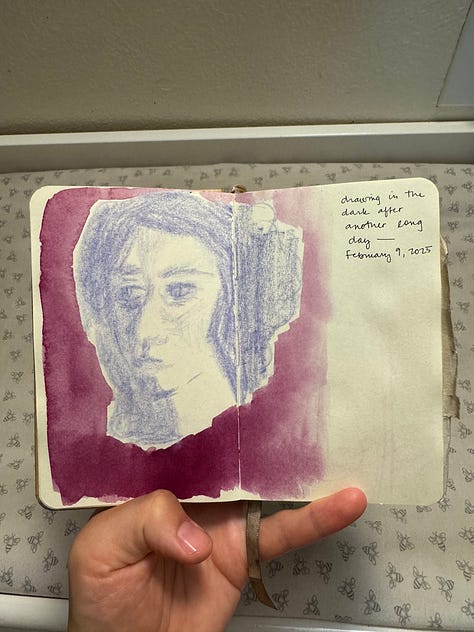

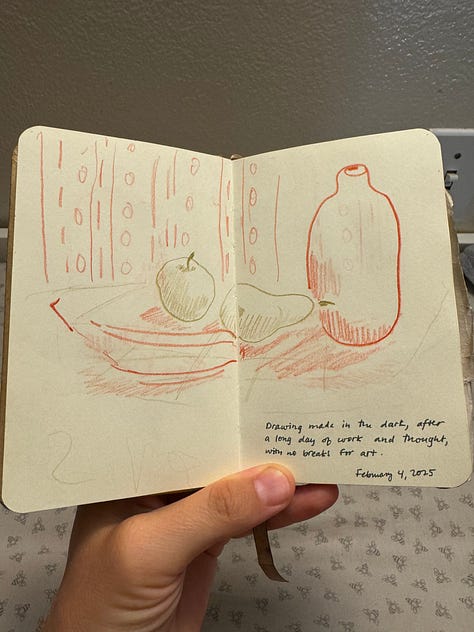

In an early effort to bring myself home to a more peaceful inner life, I had started to draw in the dark, lying next to my sleeping baby.

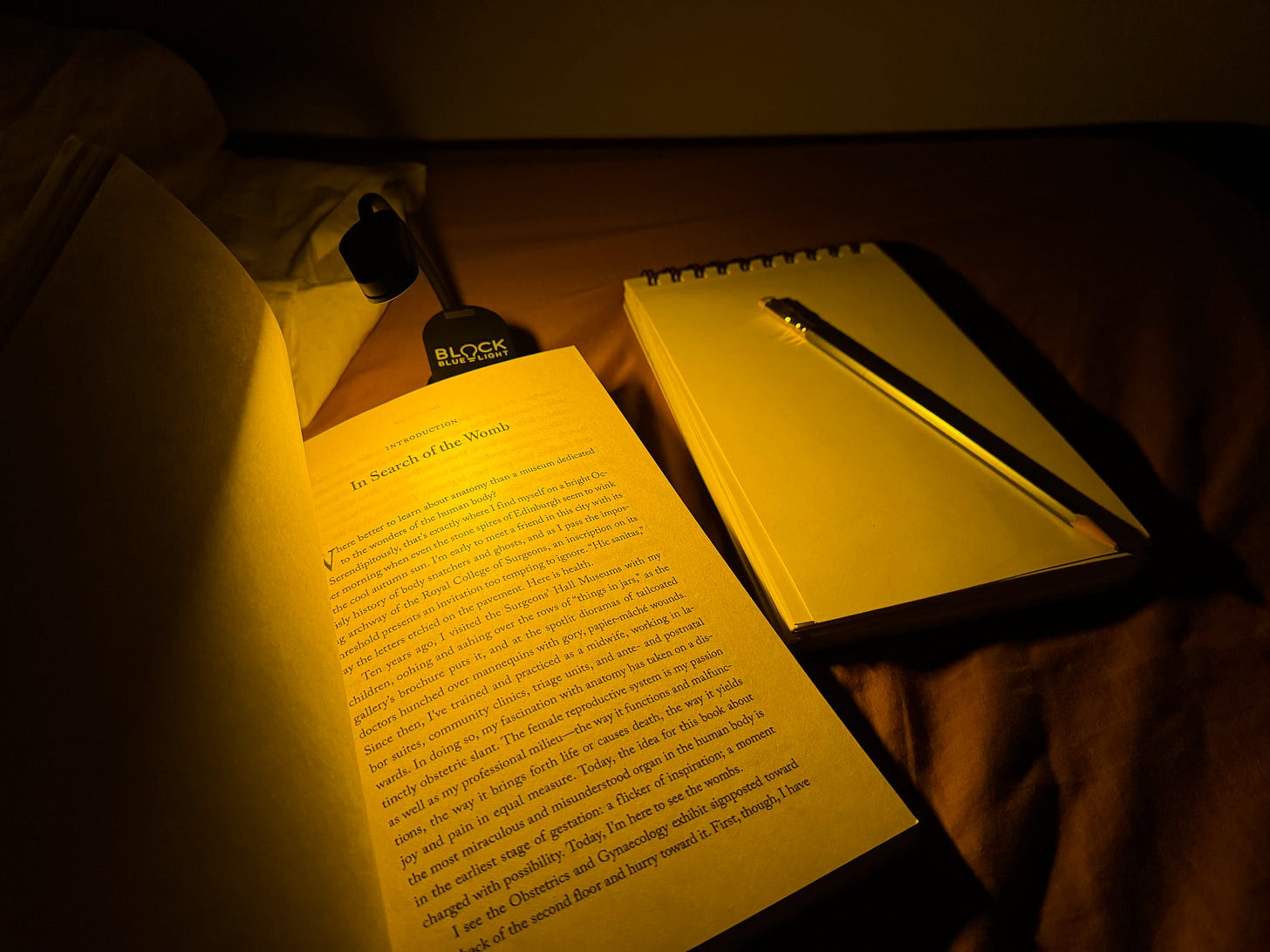

I have been challenging myself to work on a series I began in 2023, and so have been doing less work in my sketchbooks over the last month. Instead, I find myself wanting to read widely and all the time. From over a decade spent writing, I know this is in part because I’ve just made my way through the two monumental tasks of 1) completing a book draft, and 2) reading for and taking my PhD exams.

This new reading stint—filling myself up with writing on the uterus, art, parenthood and making, the nature of time, and philosophy’s views on the feminine—will end up being just that: a temporary foray, part of a wider process of regeneration.

What brought me out of postpartum depression (and anxiety) last time was maybe less the specific practice of making art, and the sense that I had of a growing vocation. A little set of actions that, most days when I took them, brought me just a snippet of hope.

Art-making still some days fills me with that feeling. I have continued with my visual practices lately not out of the hope that they’ll save me, but out of the knowledge that I have to do these things in order to want to be alive.

Reading has started to take up that sacred place that art occupied last time. It is through words, I think, that I will find my way. Even though I don’t believe strongly in the power of my own work as of late, I am constantly encountering magic in the word-worlds set up by others. Maybe these discourses, these passages and phrases, reflections and arguments, can help me construct the bridge to the person I’ll be next, as I again seek emergence from the sense of doom that has settled over me.

Rereading Art & Fear over the last couple of weeks has reminded me that we find our way through working and in the work itself. That each piece we make points, if we are paying attention, to the next thing. (It is this way with reading, too: each book or essay or article shows the way to the next one.)

The authors of Art & Fear write that

Making art now means working in the face of uncertainty; it means living with doubt and contradiction, doing something no one much cares whether you do, and for which there may be neither audience nor reward. Making the work you want to make means setting aside these doubts so that you may see clearly what you have done, and thereby see where to go next.

I’ve also been thinking about the work of Mierle Laderman Ukeles as I tackle the endless dishes and laundry. Laderman Ukeles made housework (what she calls “maintenance”) a key part of her art practice. She has even been Artist in Residence at the New York City Department of Sanitation since 1977.

Typed in one sitting, Ukeles’ Manifesto for Maintenance Art, 1969! identifies the connection between her lived experience as an artist and mother with that of Sanitation Workers: maintenance, she outlines, has to do with care and sustenance, whether this work be looking after a child, a home, or a city - it is a hidden force that keeps things going.

Inspired by the principles of her manifesto, Ukeles performed a series of maintenance art interventions in the early 1970’s in which she took on the tasks of maintenance workers.This political body of public art called attention to “invisible” labor - work that goes unnoticed and is often underpaid and undervalued, but is nonetheless essential to the upkeep of someone, something, or someplace.

The tasks of care-work are endless, but maybe if I pay attention—to the tasks themselves, to my children, to the depression and my other reactions, to the problems and questions posed by my art-work—the conjunction of all these forces in my life, and maybe a similar joining of them in yours, might point the way. Again and again. Because “the way” is not a clear path—it’s the view one foot out, and then, perhaps after a course correction or redirection, the view another foot out.

Or, as Orland and Bayles put it:

The need is to search among your own repeated reactions to the world, expose those that are not true or useful, and change them. The remainder are yours: cultivate them.

Till next time—

s

*If you’ve been reading my essays for a while, you know that we don’t gender our kids in my family—using they/them until each child self-identifies, a process my older child is working through.