As of this writing, I’m in my fourth month postpartum, or my fourth year, depending on how one conceptualizes this period of life. I also just reached 40 months breastfeeding with my older child. We’ve also just celebrated the fourth (and final) Celtic festival of the year, Samhain, which in my house overlaps with the marking of Día de los Muertos. It’s a time of significant fours. Of increasing darkness. A time to stay in, to talk about those who came before us and those who have passed on.

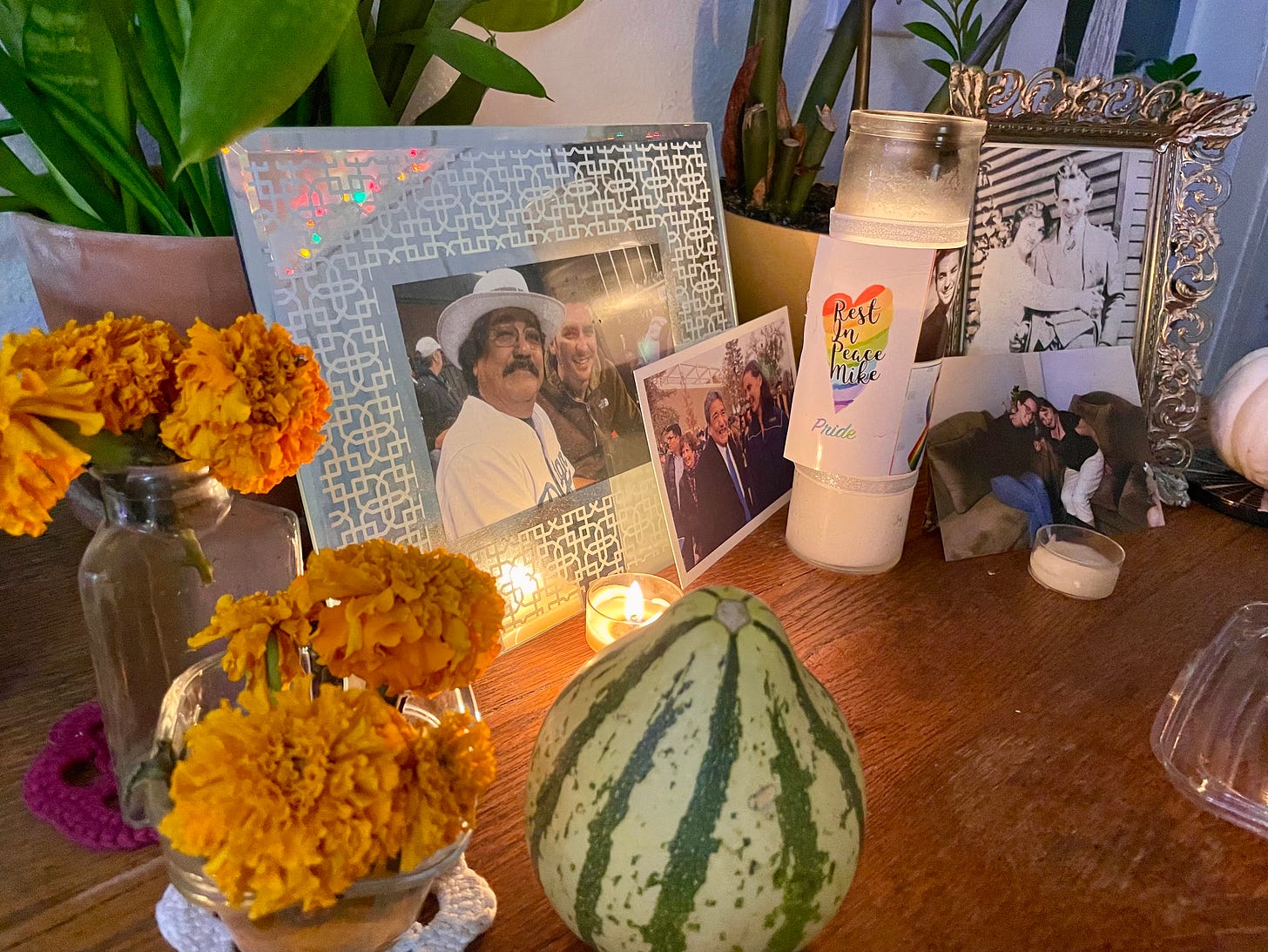

This year, that latter group—the one made up of those loved ones whose bodies have stopped—has expanded to include our beloved Papa, who appears in the first two pictures from the left on our altar, on the left in each case. He was one of those people who was so alive—singing, joking, sharing stories—that it’s been especially hard to concede that he has ceased to be. That he only lives, now, through us: those who knew him.

Grieving this time has been very different than when we lost my spouse’s brother in 2017. This time, our three-year-old is also mourning, and does so very actively, bringing Papa up every day, usually several times per day. Going through this with them has made us grieve more vocally and consistently. It hasn’t been good or bad—it’s different and is just what is.

We share pretty regularly what Papa would have said about certain things, how he would have responded. For example, our younger child had gone from 6 pounds 11 ounces at birth, to 17.5 pounds by three months of age. Every weight check, we imagine Papa’s proud response and chuckle. He loved seeing all of us grow and change, and he had been so excited about meeting and getting to know his second great-grandbaby.

All of these ways of marking time have had me thinking about when, exactly, a person stops being postpartum. When did it end for you, if you’ve experienced it? Has it ended? Will it ever? In my case, I think I’ve concluded that it won’t quite ever end. It will only fade in intensity, like so many of life’s other formative experiences.

The words post partum, from Latin, simply mean “after childbirth.” In the same way that I will always be a parent now that I’ve become one, I will always be twice over in the after. But “after” is one of those words that, because it is applied so broadly, can mask a lot of differentiation. For example, I have had two very different experiences of birth, and what postpartum meant for me the first time is drastically different from what it has meant so far this second time.

My first child was born during a time of great personal loss. My birth family had been fracturing since the year before, over so many things: the pandemic (and how each of us passed through it), the first Trump presidency and the 2020 election, vaccines, and the murder of George Floyd. It was also the year that my last grandparent died.

I’m one of nine kids. All of us were homeschooled together and none of us had particularly close relationships with either of our parents, growing up. So, many of us siblings became intensely close, often paring off—my older sister and me, my two younger sisters.

It makes sense, given these less-than-firm foundations, that those big external things, especially with so many happening at once during the pandemic, could break us up. By the beginning of 2021, and halfway through my first pregnancy, I was only talking with one of my siblings and one of my parents.

And then the birth itself, despite a very healthy pregnancy, was very difficult. I didn’t — for a single moment in the long 24-hour process — feel in control or at peace. Someone told me during those blurry hours after my unexpected C-section that I was a “great candidate for a VBAC” (vaginal birth after cesarean). In my memory, she has an absurd smile on her face. I couldn’t respond. What was there to say to such a comment while consumed by fear that the five-inch slice over the part of my body that holds in all my organs was about to just split open?

One of the things I was most worried about in the years leading up to our decision to have a child was that I would end up regretting the choice. That I would mourn all the little freedoms I would have had to give up, never recover my sense of self, and lose my chance at being a “real” writer.

During those foregoing years, I composed a poem (still unfinished) about all the limitations I envisioned, were I to decide to have a child. It went something like:

I cannot wash dishes

and read philosophy

I cannot sweep floors

and learn another language

…

Of course, since having children, I have managed to read a great deal (two of four PhD exam reading lists done, as of this writing), including some philosophy.

I have also been fortunate—thanks to a lot of people caring for me, and caring for our children—not to experience regret. Instead, despite crushing depression and anxiety, I felt, even in the most difficult period—the eighteen months following my first child’s birth—that I had been cracked open in a way that let me access a much more authentic, creative, and vulnerable version of myself.

It was this experience of self-discovery, and the everyday magic of having a child in the house, a magic that causes my spouse and I both to swing through a whole series of emotions each day, that brought me to the place in fall of 2023 of deciding, again, to try for a baby.

Pregnancy, with a toddler, and in a body that was three years older and a lot more tired to begin with, was tough. I was sick for much of it, didn’t realize I had an iron deficiency until I’d been absolutely floored by exhaustion for weeks, and experienced things I hadn’t with my first, like the spreading of the bones in my right foot (for some reason, not my left). So far, the bones haven’t gone back.

Throughout this time, we were also out protesting the genocide in Gaza, and I felt (still do) a constant mourning for all of the lives being taken—men, women and children, tiny babies; whole families—and in such horror-inducing ways, and with seeming impunity. I read about the conditions pregnant people were enduring, and thought often about how awful it would be to not be able to feed my baby, after they came.

When there are horrific things happening and, as with this one, we are directly implicated in them by our status as American taxpayers, the small amount of good we are able to do in other areas can grow to feel more important.

I donated milk with my first child, but this time around, it has been a mission in our household to bag as much milk as possible. Thanks in part to genetics, but also thanks to having access to a nutrition-filled diet, rest, and clean water, and to knowing what to do to care for my supply, I’ve managed to feed both my children and to donate (so far) over 500 ounces of milk. That is enough to keep a baby in the NICU alive for about 100 days.

Having these stats about the effect all this effort can have has been hugely motivating, and I’ve been so glad to be able to do this small thing. (If you have enough, you might also consider this. I have donated through UC Milk Bank, but there are other centers that take donations and process what they receive for use in hospitals.)

There are so many things that I wish—that we could get politicians to listen, that we could enact systems of mutual care rather than personal enrichment, that we could see the life around us as truly valuable. Doing small things doesn’t lessen the intensity of these wishes, but the little acts of care do lessen the feelings of helplessness that rise often, especially as we recently passed a year of the most extreme atrocities being broadcast around the world via our phones.

It has become somewhat common to acknowledge that we, as Americans, also live on stolen lands. I wonder about how language—however well-meaning—can erase the urgency of such a declaration, simply by normalizing it. It is as though the language itself takes the place of any action to change the situation or bring reparation.

It feels very urgent that we slow down, ask questions, learn from those we want to work with, and figure out ways forward that enact our shared values. This process is a small one, a community-based one. It probably starts at home, in the family, whatever configuration that group takes. That’s at least where I am starting, again and again and again.

Thanks for reading—

s

💙 couldn’t find the right words. I took postpartum as a medical word, I liked this idea, that the word defines the new phase of ourlives.

Love the many threads in this post. Life….